Lviv, Ukraine

It’s an enormous, hangar-like constructing, disused and decrepit, on the outskirts of Lviv. However for Mykola Piddubnyi and his colleague Irina Gavrilov, the native entrepreneur’s reward was a godsend, permitting them to maneuver their increasing wartime provide operation out of Gavrilov’s tiny condo. The day I visited, there have been dozens of wood pallets unfold out throughout the massive house: one cluster—possibly 40 cardboard containers—for baked items, one other for giant plastic buckets full of dumplings, nonetheless different areas for canned meals and toiletries, even a pallet piled excessive with crutches and wheelchairs.

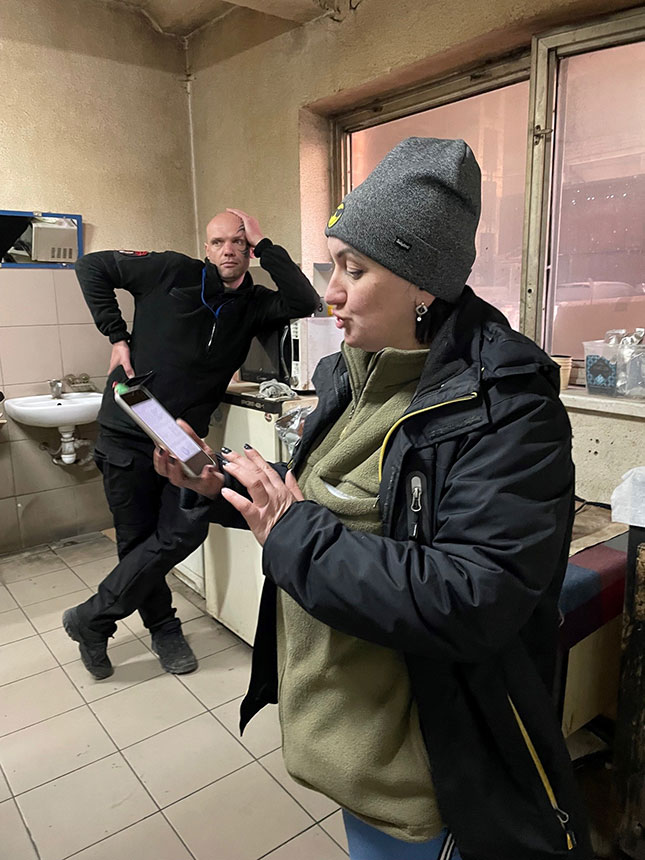

However Gavrilov guided us previous all that to the realm that meant most to her, with the containers she and a crew of associates and family pack each day for troopers serving on the entrance traces. In contrast to the opposite containers within the warehouse, destined largely for civilians, every of those cartons was an act of affection: a hand-picked combine of things to maintain a soldier for every week to 10 days. Canned meat, dried soup, pasta, sauerkraut, cookies, cigarettes, even toothpaste and bathroom paper: the contents diverse from field to field, every packed a bit in a different way, with an unmistakable human contact.

Doesn’t the federal government present meals for fighters, I requested? “Not all the time,” stated Piddubnyi. “It’s laborious to get to distant, rural Donetsk. Once I served there in 2015, we drank from puddles and ate frogs.” So this time round, folks like Piddubnyi and Gavrilov are serving to, doing no matter is critical to help the battle effort.

I visited Lviv in early April, simply as the primary focus of the battle in Ukraine was shifting nearer to Russia, from the central Kyiv area to Donbas within the east. As soon as an vital medieval metropolis and later an outpost of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Lviv had hardly been touched by the Russian invasion. Nonetheless, even because the combating raged greater than 800 miles to the east, it was clear to a customer that this was a metropolis at battle.

Site visitors out and in of the middle snarled at navy checkpoints. A curfew emptied the streets at 10 p.m. On my first evening there, an air-raid siren despatched me racing to the basement of my resort. In line with native estimates, a whole bunch of hundreds of what migration specialists name “internally displaced individuals” (IDPs) had swelled the inhabitants of the town by greater than 50 p.c.

However much more placing, and arguably a extra consequential change, was how the overwhelming majority of Lviv residents had put their lives on maintain, repurposing no matter they did for work and reorganizing their days to bolster the battle effort.

“Most individuals I do know have dropped every thing,” stated Anna Swanson, a former actual property supervisor now centered on humanitarian help. “They’re utilizing their very own time and their very own assets to help Ukraine.”

Town’s largest artwork museum had postponed occasions and put its work into storage, reinventing itself as an enormous warehouse for humanitarian provides. A policy-research nonprofit had suspended its work and transformed its elegant townhouse workplace right into a recruitment middle for Territorial Protection militia. Town vacationer company was serving as a media hub, supporting international journalists arriving to cowl the combating.

White-collar, blue-collar, younger and previous, people and organizations, private and non-private: to name these efforts “civil society” hardly appeared to seize their scope or scale. This was a whole metropolis mobilized to do its half to win a battle.

“There aren’t any bullets whistling by us, no missiles or explosions,” defined Roman Andreiko, co-owner of the nation’s largest TV information channel. “However that is additionally the entrance line. Who can say that what we’re doing is much less vital?”

Nothing captured the town’s transformation extra vividly than a go to to the Lviv Nationwide Artwork Gallery. Like a lot of the Lviv battle effort, the revered state-run establishment was now dedicated to logistics: amassing and transport provides to elements of the nation reduce off by Russian bombardment.

Three flooring of a former cultural middle had been emptied and divided into what employees referred to as “departments”: separate rooms for mattresses, blankets, garments, groceries, child meals, hygienic merchandise, medical provides, and digital gear. Volunteers scurried out and in. Some have been unloading containers of donated items arriving from overseas. Others have been sorting gadgets into big piles and repacking them in new containers to be carried out to ready vans, the place nonetheless different volunteers stood prepared to move the provides.

Museum director Yuriy Viznyak, a profession civil servant, advised me that he made the choice to transform the gallery on the battle’s first day. “Many individuals I knew have been leaving the town, heading for Poland or Hungry,” he recalled. “However I made the choice to remain. Even then, I believed Ukraine would win, and I needed to do my half.”

Since then, the middle has obtained greater than 20,000 requests for assist—from native municipalities, hospitals, navy models, nonprofits, and particular person IDPs as distant as Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhya, a full day’s drive to the east. Museum employees compile requests and maintain a working listing of essential gadgets. On the day I visited, dried meat and sausage topped the foodstuffs listing. Razors have been high precedence amongst home goods. The director wished protecting navy gear—helmets and bulletproof vests.

Spectacular because it was, Viznyak emphasised, the museum warehouse is just one hub of a a lot bigger provide effort: an unlimited, decentralized internet of people and organizations in Lviv, some working collectively, many working independently.

Different provide depots, private and non-private, have been bobbing up across the metropolis. The museum’s pickups and deliveries have been dealt with by another person—impartial groups of volunteers with their very own vehicles and vans. Alongside provides shipped in from overseas and cash wired from throughout Europe, the director singled out one native aged lady who had not too long ago delivered three pillows. “We now have extra requests than we are able to deal with,” he defined. “However fortunately we’re not working alone.”

Anna Swanson additionally made the choice to upend her life on the primary day of the battle. Born in Ukraine, she had spent greater than a decade within the U.S. earlier than returning to the area 5 years in the past. Earlier than the battle, she made a residing serving to to revive and handle rental properties within the historic middle of the town. The day after the Russians invaded, she drove to the border with a automobile filled with blankets and heat clothes for the refugees, largely ladies and kids, streaming from Ukraine into Poland.

“Massive organizations transfer slowly,” she defined, “and in these first days, it was simply bizarre, random folks like me.” However issues have been continually altering, and inside days, there have been dozens of teams offering reduction on the border—humanitarian operations, giant and small, lots of them organized overseas. So Swanson expanded her scope, shopping for humanitarian provides in Poland and delivering them inside Ukraine.

Then, a number of weeks later, she noticed that many different teams have been doing that, too, and she or he refocused her efforts once more. “The battle doesn’t stand nonetheless,” she defined. “What’s wanted adjustments each day. You establish the necessity that day or that week, and also you reorganize to do it.” Her new mission: shopping for medication in Poland and delivering it to hospitals in Ukraine.

The brand new operation provides each navy and civilian hospitals. What’s lacking is commonly pretty fundamental: atropine for surgical procedures, insulin, adrenaline. Different amenities lack rarer or perishable medicines. Ukrainian medical doctors write the prescriptions; there aren’t any boundaries on the border. Swanson’s precedence is hospitals treating medical casualties, and she or he and her crew go wherever they may also help—to Kyiv, Kharkiv, Krematorsk, and deep into the Donbas area.

The operation has grown quickly into greater than Swanson can deal with by herself. However it hasn’t been laborious to search out assist. She referred to as associates, who referred to as associates, who referred to as different associates, and earlier than lengthy, she had a crew of about ten volunteers—some driving, some loading and unloading, lots of them chipping in their very own cash to purchase provides. There was no formal group, only a widespread trigger and a shared sense of urgency.

Like many related advert hoc networks which have sprung up in Ukraine and in surrounding nations flooded by refugees, Swanson’s community is constructed on belief—members are all associates of associates, even when they don’t all know each other. Folks talk largely just about, on an instant-messaging platform. Volunteers tackle no matter roles they suppose they’ll deal with. They do what they’ll for so long as they’ll, and the community grows and shrinks, adapting to deal with no matter is occurring on the bottom.

The problem, confronted ultimately by each one of these small teams, is funding—cash to pay for provides, whether or not in Ukraine or overseas. In Swanson’s case, the answer was an American-led, Kyiv-based nonprofit, Assist Ukraine 22, that raises cash within the U.S. to help humanitarian reduction inside Ukraine.

The operation is an offshoot of a for-profit enterprise—a small government-relations consulting agency—working in Kyiv for greater than a decade. Like everybody he knew, proprietor Brian Mefford made the choice to pivot on the day the Russians invaded, switching from paid consulting to humanitarian help. The brand new nonprofit raised just below $1 million within the first seven weeks of the battle, a lot of it on Wall Avenue and amongst Mefford’s associates in Republican internationalist circles.

Initially, the group’s essential focus was evacuations: driving individuals who wished to depart Ukraine in a foreign country. However like Swanson’s smaller, casual group, Mefford’s group has developed, and it now works primarily to supply medical help.

The operation depends on leverage: multiplying the facility of the cash it raises by investing shrewdly and enlisting others. Mefford and a small core crew drive some provides throughout the border themselves. “But when others can do the job quicker and higher,” he says, “we pay them to do it.”

One other of his favourite ways: “rescuing stranded cargo.” Martial regulation prevents Ukrainians from sending cash overseas—even cash to ship wartime provides into the nation. However transport is comparatively cheap, usually a small a part of any provide value, and Mefford could make up the distinction, in a single current case offering simply $1,400 to move $30,000 price of donated medication and different provides from Dusseldorf, Germany, to Lviv.

Greater than three-quarters of the nonprofit’s funding goes to help homegrown Ukrainian reduction efforts: grants to native governments, health-care suppliers, nongovernmental organizations, and teams like Swanson’s. Most grants are small: from $2,000 to $10,000. Grantees should make a proper request and doc the necessity they’re addressing. Years of expertise working in Ukraine assist Mefford vet potential grantees. In different instances, like Swanson’s, he begins with a small, one-time award designed to check what an applicant can do.

Swanson handed with flying colours, delivering a vanload of drugs from the border to Donetsk, and she or he’s now a part of the nonprofit’s quickly increasing operation: some 70 employees and volunteers, virtually all of them Ukrainian—a community of networks serving to to maintain different Ukrainians alive.

Irek Czubak’s operation can be a community of networks, however extra casual than Mefford’s, and its tentacles might attain even deeper into Ukrainian society, with grassroots volunteers like Mykola Piddubnyi and Irina Gavrilov doing a lot of the work within the subject.

Piddubnyi doesn’t seem like a typical caregiver. A tricky former soldier with a shaved head and facial tattoo based mostly on Mike Tyson’s trademark inking, Piddubnyi determined to not reenlist when Russia invaded in February. Based mostly on his expertise serving in jap Ukraine within the final battle with Russia, from 2014 to 2019, he felt that he may do extra good from outdoors the armed forces, supplying meals, medication, and matériel to troops and civilians on the entrance traces.

“A variety of volunteers are afraid to drive into the combating,” he explains. “I’m a soldier. I’ve been there. I’ve been shelled. I’m not afraid.” If something, the extra harmful the mission, the extra he appears drawn to endeavor it.

He drives a small, shrapnel-scarred automobile, packed to the roof with cardboard containers, and is often accompanied by two getting older cargo vans, additionally crammed to capability. He says that roughly 70 p.c of what he takes into the battle zone is for civilians, the remaining for navy models. His priorities begin with kids and the aged, the nearer to the entrance traces, the higher.

He depends on contacts within the armed forces to assist him establish the most secure routes. Generally it’s an official “inexperienced hall”—a highway designated by the federal government for humanitarian transports and evacuations. In different situations, it’s only a again highway, typically unpaved, and it’s commonplace for his little convoy to drive 1,000 kilometers a day.

Piddubnyi and Gavrilov work as companions on the middle of a community very similar to Swanson’s—spontaneous, casual, agile, and ever-changing, as volunteer members come and go. Piddubnyi depends on roughly a dozen volunteers. Gavrilov runs the warehouse in Lviv and attracts on what she says is an online of about 90 folks to cook dinner, cadge, and buy meals and different provides.

One group of older ladies in a close-by village works in shifts in a borrowed kitchen baking bread and cookies. One other village sends dumplings—in line with Gavrilov, three busloads a day. Nonetheless different ladies preserve meat in repurposed jelly jars. One batch I noticed featured handmade labels: “Come again alive and produce this jar again to Lviv.” Nonetheless different labels, affixed to containers of baked items, have been drawn by native kids: brightly coloured pictures of every thing from tanks to rainbows that Gavrilov says assist to spice up troopers’ morale.

The community operates on a shoestring. Each Piddubnyi and Gavrilov have given up their day jobs. He borrows from associates to pay his lease. She has depleted the cash she had been saving for her son’s schooling, utilizing it as a substitute to buy provides. His largest want, he says, is money to cowl the price of gasoline. Her essential criticism on the day I visited was a dip in donations of nonperishable groceries.

This is the place Irek Czubak is available in, one in all Piddubnyi and Gavrilov’s largest suppliers. An evangelical Christian Pole, Czubak has been working charitable organizations in Poland and Ukraine for greater than 25 years. Certainly one of his priorities earlier than the battle was connecting Jews and Christians, and when the Russians invaded, this work paid off in an unlimited internet of contacts on each side of the border—what Czubak describes as “Jews, Christians and atheists” he can name on for assist delivering humanitarian help.

One previous buddy, a high-ranking official within the Ukrainian border management, helped Czubak and his brother evacuate 15,000 refugees within the first eight days of the battle. Then, when most different reduction teams have been placing up welcoming tents on the Polish aspect of the frontier, the identical official gave the brothers permission to work on the opposite aspect, in Ukraine, the place the necessity was much more pressing—offering meals and heat clothes to refugees ready in line to be processed, typically for so long as two to a few days within the bitter chilly.

Nonetheless one other connection, to the Jewish Group Middle in Krakow, has offered beneficiant funding for Czubak’s operation. He appears to folks like Piddubnyi and Gavrilov—locals in Lviv, Kyiv, Rivne, Kharkiv, and elsewhere with entry to warehouses and drivers.

Additionally important: sources that may present intelligence—church buildings, synagogues, native officers, and navy commanders who can establish precisely what sort of assistance is most desired. “It adjustments each day,” Czubak says. “And also you’re no use except what you’re sending is what’s wanted that day.”

Czubak’s largest current coup: somebody launched him to a French businessman with ties to a gaggle of villages in Northern France that wished to contribute to the Ukrainian reduction effort. To this point, they’ve despatched eight truckloads—massive 18-wheelers, every carrying greater than a ton of meals—and eight extra have been promised.

One arrived at Gavrilov’s Lviv warehouse the day I visited, a great addition for quickly diminishing provides. Two days later, Piddubyni and his convoy of battered vans have been on the highway, en path to Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel, previously occupied cities within the Kyiv area from which Russian troops had simply withdrawn.

At the alternative finish of the socioeconomic spectrum from Piddubnyi and Gavrilov, the founders of Ukraine Wants Wheels are younger professionals in Kyiv—monetary analysts, legal professionals, and affect buyers, lots of whom have frolicked within the U.S. Searching for a strategy to assist in the primary days after the invasion, a number of of them stumbled independently on the concept of shopping for automobiles, a virtually ubiquitous necessity in war-torn Ukraine. Reduction staff want automobiles to evacuate refugees. Folks bringing provides into the nation want automobiles on each side of the border and within the inside. Medical personnel want ambulances and transports.

However arguably the sharpest want and essentially the most important to the battle effort is among the many armed forces—particularly Territorial Protection models and volunteer battalions. Ukraine’s profitable technique within the first part of the battle relied on agile, guerrilla-style fighters who may infiltrate enemy positions and destroy tanks and artillery. These troops require Jeeps and pickup vehicles. Different models lack vans to ship provides and transport wounded troopers. Among the many most crucial requirements: four-wheel-drive automobiles that may go off-road, avoiding Russian mines and artillery by slicing by fields and forests. All these conveyances are briefly provide in Ukraine.

The younger males who would ultimately come collectively in Ukraine Wants Wheels began small: people shopping for automobiles someplace in Western Europe, typically with their very own cash or funding from associates and family, then driving them throughout the border separately. The breakthrough got here when the group realized that it had the experience to function at scale, fundraising within the U.S. and Europe to purchase and transport automobiles in bulk.

The transport operation is comparatively easy. One set of volunteers drives the automobiles from wherever they’re bought to the Ukrainian border. A second group masses them on a tow truck—by far the quickest strategy to get by clogged border checkpoints. A 3rd crew takes care of the final leg—from the frontier to a chosen navy unit the place a commander has requested a car, whether or not for transport or different functions. Once I visited in early April, Ukraine Wants Wheels had delivered 45 automobiles.

More durable and extra advanced than coordinating transport was constructing an entity to maintain the operation—a semiformal crew of volunteers that would operate on a nationwide scale. One group in Kyiv coined a reputation for the unit and labored, as co-founder Valerii Kondratenko put it, to “create a model.” Different members of the community reached out to charitable organizations within the U.S. and Europe, constructing partnerships that will permit the group to channel funding into Ukraine.

One member who requested to stay nameless defined the problem: “It’s a lot more durable to boost cash for the military than for humanitarian help. Refugees and IDPs are a symptom. What’s inflicting the struggling is the battle. However there aren’t many donors who need to hear that or need to write checks for the navy.”

Ukraine Wants Wheels isn’t the one group I encountered funneling provides to Ukrainian fighters. Come Again Alive is a long-established nonprofit launched in response to the final Russian invasion, in 2014. Near the Ukrainian armed forces however solely personal—it receives no state funding—it raises cash largely inside Ukraine and spends it completely on high-tech gear, not fundamental gear like helmets or bulletproof vests.

A lot of the know-how is “twin use”—it has civilian and navy purposes—and Come Again Alive provides no weaponry. “We need to shield life, not take it,” defined fundraising director Oleg Karpenko. However the gear his group offers is crucial for the battle effort: gadgets like night-vision goggles, thermal-imaging cameras, and quadcopter drones.

Karpenko says donations soared after the Russian invasion in February. Within the battle’s first month, the group raised ten instances what it took in from 2014 to 2021. However like just about all of the teams I encountered in Ukraine, Come Again Alive is seeing contributions drop because the battle drags on and donor fatigue units in.

Civil society shouldn’t be sufficient. Much more pressing than fundraising, at the same time as their operations broaden, each Come Again Alive and Ukraine Wants Wheels echo Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s requires heavier weaponry. Pickup vehicles, drones, and different dual-use know-how bought by civil-society teams are higher than no gear. However they received’t be sufficient to win the battle.

“The automobiles we herald are efficient for defensive operations,” defined Kondratenko of Ukraine Wants Wheels. “But when we need to regain territory or recapture our land, we are going to want one thing very completely different—gear that provides us the identical functionality as our enemy.”

“We’d like long-distance artillery, long-range air-defense methods, tanks, and fight plane,” stated Karpenko of Come Again Alive. “No nonprofit group on this planet should buy that type of weaponry. That’s a job for presidency—authorities to authorities.”

“Nonetheless,” he concluded gravely, reiterating what I had heard from many individuals I spoke with in Lviv, “even when our worldwide companions don’t help us, we are going to carry on combating with no matter we have now. Our nation has proved what we are able to do—proved we are able to battle, proved we are able to help our fighters. And we are going to proceed combating till the top.”

High Photograph: The canteen of a former movie show, now a shelter for displaced individuals—a location provisioned by Mykola Piddubnyi and Irina Gavrilov (Photograph: Adam Reichardt)