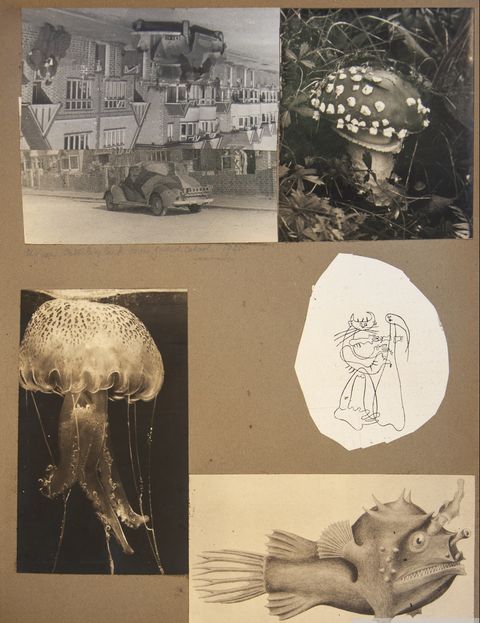

Not way back, in a espresso desk e book about Surrealist and photojournalist Lee Miller, I noticed a curious photograph of Miller sprawled bare on a garden, her pores and skin coated in greenish grime and chunks of turf.

“Lee Miller in camouflage,” learn the caption.

A short passage casually defined that Surrealist artist Roland Penrose—Miller’s lover and later her husband—had used the photograph in lectures on wartime camouflage. He and different Surrealists had, at first of the Second World Struggle, fashioned a camouflage providers unit and had been later absorbed into official camouflage roles within the British army.

Wait—what?A Surrealist camouflage unit? That will need to have been absurdity central, I believed, imagining Salvador Dalí holding court docket in a bunker, sporting a diving swimsuit and a lobster hat. However after I researched the subject in earnest, I discovered that the work of the Surrealist camoufleurs was lethal critical, and even arguably helped to show the tide of the battle. Then, these previous few weeks, with the horrific Russian battle in Ukraine, the topic took on sudden urgency for me, with its David-and-Goliath theme of civilians doing every thing they might to outlive and assist repel a brutal army assault on their nation.

Due to their longtime obsession with mimicry and visible deception, the Surrealists had been peculiarly effectively suited to camouflage work, which turned crucial to WWII’s new period of aerial warfare. A passionate “camouflage evangelist,” Penrose was instrumental in getting Allied forces to see camouflage as a weapon that might assist flip an overwhelmed underdog right into a victor. “It was Penrose who acquired the military to take camo significantly,” says Rick Stroud, historian, filmmaker, and creator of The Phantom Army of Alamein.

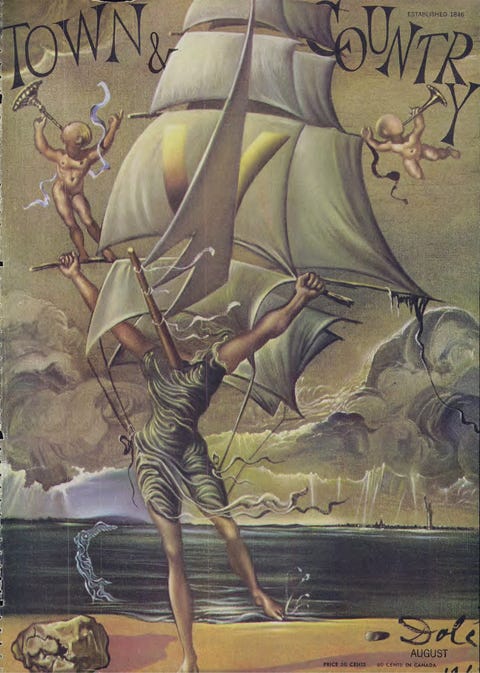

Not too long ago the artwork motion has impressed a major resurgence of curiosity. The Metropolitan Museum of Artwork in New York and the Tate Fashionable in London have co-curated an ongoing, vital exhibition on international Surrealism; style designers have rolled out Surrealist-inspired collections; Surrealist works have been fetching document costs at public sale. But Surrealists’ vital wartime actions seem to have been largely forgotten.

Antony Penrose—son of Roland Penrose and Lee Miller—is trying to assist treatment that. On Might 26, a five-month exhibit about Penrose, Miller, and Surrealist camouflage will open on the couple’s former dwelling, Farleys Home & Gallery, in Sussex, England. A objective of the exhibition: to assist restore public reminiscence of the wartime actions of Penrose, Miller, and their friends. Forward of this present, the Lee Miller property has generously shared with City & Nation a number of war-era pictures of the Surrealists engaged in camouflage work—a few of them by no means beforehand revealed.

Right here is the story of when the Surrealists went to battle, how they used artwork to assist thwart the fascist onslaught, and finally assisted in bringing Britain a desperately wanted victory in opposition to Hitler’s armed forces.

At first look, Roland Penrose doesn’t seem to be the most certainly advocate for turning artwork right into a guerrilla warfare tactic. Born in 1900 in London to a rich Quaker household, Penrose was a conscientious objector in World Struggle I. As an ambulance driver in Italy throughout that battle, nevertheless, he noticed firsthand the horrors of battle, and afterward “started to see artwork because the salvation of the world,” based on Antony Penrose.

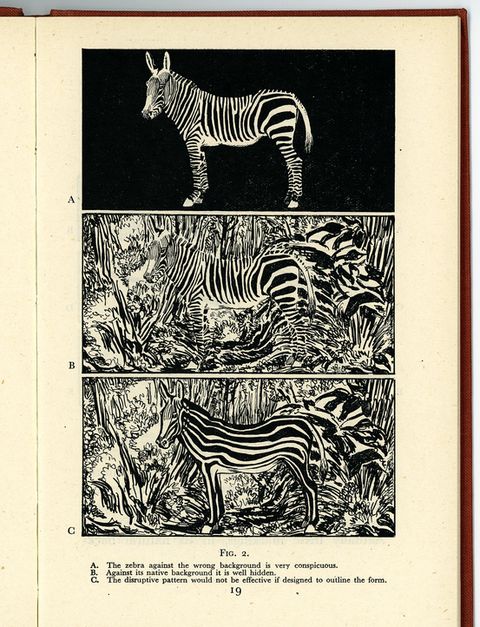

After the battle, Penrose finally moved to Paris, the place he met and labored alongside cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. In Braque’s work particularly, Penrose was drawn to the “strategy of deception,” during which the artist painted objects to make them seem like one thing else, akin to marble or grained wooden. Additionally of curiosity to Penrose: how cubist sample disruption strategies had been tailored in the course of the First World Struggle to assist camouflage warships.

In Paris, the Surrealists—who included Salvador Dalí, Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara, Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, and Man Ray, amongst others—typically gathered in cafés in St. Germain des Prés or Montmartre. Like Penrose, among the different Surrealists had served in WWI, and collectively they despaired over a lot of Europe’s terrifying descent into fascism, which was “extinguishing one after one other the liberties amongst which we’ve moved in our carefree method 10 years earlier than,” recalled Surrealist artist Julian Trevelyan.

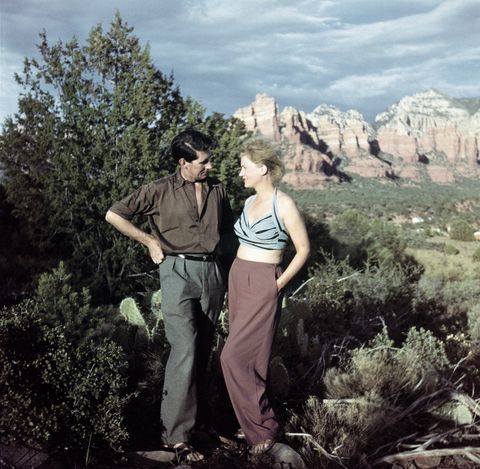

When Hitler’s forces invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, setting off the Second World Struggle, Penrose was in France with Miller. They’d met two years earlier at a Surrealist ball in Paris, the place Miller—a photographer, Vogue cowl mannequin, former lover of photographer Man Ray, and Surrealist artist and muse—captivated Penrose at first sight. Fortunately for him, the attraction was mutual.

Penrose and Miller swiftly boarded a ship again to England. On the boat they bumped into Trevelyan. The artists collectively acknowledged that there was no method to escape this “unbelievable nightmare,” mentioned Trevelyan. “The battle in opposition to fascism [had now been] dropped at our doorstep. We [had to] take part, whether or not we favored it or not.”

But they had been decided to discover a method to battle this overwhelming existential menace with out actually combating. “I used to be by no means a born hero,” Penrose mentioned later, “[and] I knew I might by no means be a lot good at killing folks.”

There on the boat to Southampton, the little group determined that they might battle fascism with artwork. Extra particularly, they might attempt to put their Surrealist outlook and abilities to sensible use in camouflage work.

This determination was whimsical and sensible on the similar time. In spite of everything, camouflage was the apply of disguising objects or making them appear to vanish altogether. Artists from all backgrounds would finally change into wartime camoufleurs, however the Surrealists had already been experimenting with such visible trickery for years.

“All via the Nineteen Thirties, the Surrealists had been fascinated by something within the pure world that pretended to be one thing else,” says Samantha Kavky, artwork historian and creator of the article “Surrealism, Struggle and the Artwork of Camouflage.” “There’s an obsession with deception, and this concept of pretending to be one thing aside from what you’re.”

Artwork could possibly be the salvation of the world, Penrose as soon as thought. Now got here the onerous work of determining how you can translate this idea into apply. He and his mates ready to assist bamboozle the enemy.

When Penrose, Miller, and Trevelyan arrived in London, the town was already on wartime footing. An air-raid siren was blaring. Barrage balloons hovered within the sky above. The town was like “some enormous, disturbed ant heap,” recalled Trevelyan.

Together with surrealist artist Stanley William Hayter, who had seen camouflage in apply in the course of the Spanish Civil Struggle, Penrose, Trevelyan, and a number of other different artists based the Industrial Camouflage Analysis Unit, a industrial operation that may create camouflage designs to cover factories and different issues. The British had been steeling themselves in opposition to imminent aerial assaults from Hitler’s Luftwaffe, and panicked civilians tried slap-dash DIY makes an attempt at camouflaging factories, houses, and depots, portray unconvincing decoy designs throughout roofs.

“Individuals appeared to suppose that … [a] rash of squiggly inexperienced patterns … had been a attraction that one way or the other purchased them immunity from the unknown hazards of battle,” Trevelyan mentioned. But he and his colleagues on the new child Industrial Camouflage Analysis Unit had been additionally nonetheless amateurs. The issue: “We had none of us executed a lot flying,” mentioned Trevelyan, “and the sample of the world from above is learn very otherwise from the best way during which we had supposed.”

Undeterred, they used the Camouflage Unit as a laboratory, mocking up designs for disguising weapons and different army gear. The Camouflage Unit folded in June 1940, simply as Paris was falling to the Germans. Penrose and others from the workforce had been quickly known as up for army service and absorbed into official camouflage operations.

Unsurprisingly, the transition to military life was not straightforward among the artists, who had lengthy railed in opposition to the institution and sometimes embraced flamboyance. (Dalí, for instance, had lately proven as much as a surrealist present in London sporting a diving swimsuit—full with a helmet—and flanked by two enormous, white borzois.) “It took a lot time to get the cling of the army machine,” as filmmaker-turned-camoufleur Geoffrey Barkas dryly put it.

This was actually true for Trevelyan, a famous eccentric who had donned giant black felt hats and carpet slippers throughout his Cambridge days. Nicknamed “Lofty” by one sergeant, Trevelyan introduced his personal thrives to army life (“I attempted onerous to take it significantly,” he later mentioned), festooning his uniform with a “little cane to hold and a decorative black and gold walking-out cap.”

After finishing a six-week primary coaching and camouflage course, Trevelyan was assigned to a unit that disguised giant concrete “pillbox” forts being constructed throughout the British Isles to halt German tanks in case of an invasion, which now appeared inevitable. (Simply a number of months earlier, following the disastrous defeat and retreat of British forces at Dunkirk, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had given his “Struggle on the seashores” speech, rallying his countrymen and girls to arm themselves and put together to battle the enemy on their seashores, streets, and fields.)

To disguise the pillbox constructions, “we camouflage officers got full rein to our wildest fancies,” Trevelyan mentioned later. He and his colleagues reworked the pillboxes into homes with thatched roofs, caravans, haystacks, and cafés. His designs turned more and more elaborate: “I had erected garages full with petrol pumps [and] ‘Closed for the Season’ [signs], public toilets, cafés, chicken-houses, and romantic ruins.”

Trevelyan was then dispatched to North Africa, the place camouflage was about to play an enormous position in serving to British forces there flip the course of the battle. He and his fellow troopers “had been all made to put on little identification discs spherical our necks. On these we had been required to inscribe our identify, quantity, and faith.” For faith, Trevelyan proudly wrote “Surrealist.”

“I’ve typically questioned,” he mentioned later, “what rites would have been carried out by a conscientious Commanding Officer.”

Quickly Surrealists across the globe had been performing as “evangelists” of camouflage, as Trevelyan put it. In Australia, Max Dupain turned a member of the Sydney Camouflage Unit. In New York Metropolis, Arshile Gorky taught a camouflage course. “An epidemic of destruction sweeps the world right now,” he informed his college students. “What the enemy would destroy, nevertheless, he should first see. To confuse and paralyze this imaginative and prescient is the position of camouflage.”

Additionally safely ensconced in America, Dalí wrote an article for Esquire arguing that the Surrealists had lengthy proven how objects could possibly be rendered invisible and suggested Allied army forces to take word. (On this article, Dalí additionally tried to take the lion’s share of credit score for the motion’s work in mimicry, and brag-hinted that he personally had unlocked the secrets and techniques of complete camouflage however couldn’t reveal them as a result of nationwide safety issues.)

But although defensive camouflage (nevertheless ineptly carried out at first) had been embraced on the house entrance, Allied army leaders nonetheless wanted to be satisfied that the camouflage recreation have to be upped on battlefields. For the reason that finish of World Struggle I, the British army had reduce camouflage budgets and did not develop new camouflage items and practices.

“When [the war] began, the military had fully forgotten about [camouflage], and thought it was a query of placing twigs in your hair and hiding your automobiles below bushes,” says Peter Forbes, creator of Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage.

Roland Penrose, some specialists say, was a key participant in convincing the British army to take camouflage significantly. “Camouflage isn’t any thriller and no joke,” he asserted. “It’s a matter of life and loss of life— of victory or defeat.”

After his industrial camouflage operation closed, Penrose turned a camouflage skilled and trainer, first with a guerrilla coaching operation after which for the Struggle Workplace. He lectured throughout the nation, typically on a cruel schedule. Coaching troopers, most of whom weren’t precisely artistically inclined, within the artwork of camouflage proved difficult. To assist advance his trigger, Penrose conscripted his most enjoyable asset: Lee Miller.

Miller—then busy photographing blitzkrieg devastation in London—actively supported Penrose’s camouflage work. She photographed his camouflage fashions within the British Vogue studio, so he may use the photographs in lectures. When he wanted to check new inexperienced camo make-up, she gamely stripped down and coated her face and full physique with it. She additionally posed for colour pictures, bare apart from full-body camouflage cosmetics, web stretched loosely over her physique, and a few strategically positioned turf throughout her thighs. “If camouflage can cover Lee’s charms,” Penrose informed troopers, “it could possibly cover something.”

His lectures subsequently turned extraordinarily fashionable, with troopers returning two or 3 times, all of a sudden bursting with enthusiasm in regards to the artwork and significance of camouflage. Miller later talked “about these camouflage actions with delight,” says Antony Penrose.

“She realized that Penrose was doing one thing important and vital,” he provides. “And this work underlined the truth that she wished to make a contribution to the battle effort as effectively.”

Miller would certainly quickly make an indelible mark as one among simply 4 feminine photographers credited as official battle correspondents with the U.S. armed forces. She documented their advance throughout Europe, capturing on movie D-Day’s aftermath in Normandy, the liberation of Paris, horrific scenes at German focus camps, and Hitler’s destroyed former retreat in Berchtesgaden, flames nonetheless hovering from the construction.

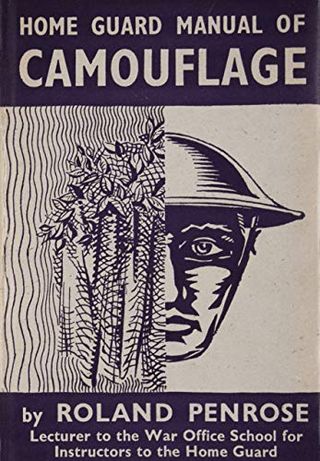

Penrose turned a gamechanger in 1941, when he revealed the Residence Guard Guide of Camouflage (which might be reissued this month for the primary time for the reason that battle). In its pages, Penrose confirmed how you can accomplish seemingly unimaginable visible deceptions: how you can create dummy weapons and human decoys; how you can good the artwork of the booby entice; how you can make shadows from automobiles “vanish”; how you can create a “phantom platoon” that might patrol and but “stay virtually invisible.”

Whereas Penrose drew on influences starting from historical warfare to camouflage within the pure world, his Surrealist ardour for mimicry was obvious all through the e book. Patterns, textures, shading: all these inventive units now took on critical army foreign money. In true avant-garde artist type, Penrose suggested on how junk, garbage, and scavenged pure supplies could possibly be repurposed to create dummy vehicles, tanks, and buildings. He made drawings of varied vision-baffling sniper fits that may assist sharpshooters seem invisible in opposition to their backgrounds.

Hundreds of miles away, at a British camouflage operation in Egypt, camouflage skilled Geoffrey Barkas was about to make use of these classes to assist change the course of the battle. He had educated briefly alongside Penrose and Trevelyan in England, calling himself “the cuckoo in a nest of artistic artists.” Now in Africa, Barkas elevated the artwork of camouflage and army decoys, noticed Trevelyan, who himself arrived in Egypt in early 1942.

On September 17, 1942, Barkas was summoned by headquarters to debate an imminent top-secret army operation. British Area Commander Bernard Montgomery was planning an offensive in opposition to German forces below Area Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had forcefully reversed an early British advance throughout North Africa. The assault would happen within the northern Egyptian desert, close to the city of El Alamein.

Barkas and his workforce had been informed to mastermind a large camouflage and deception marketing campaign that may distract and confuse German forces throughout “Operation Bertram.” The problem was irresistible but unenviable, “as a result of the desert is so open, so pitiless in exposing troop positions,” says Peter Forbes.

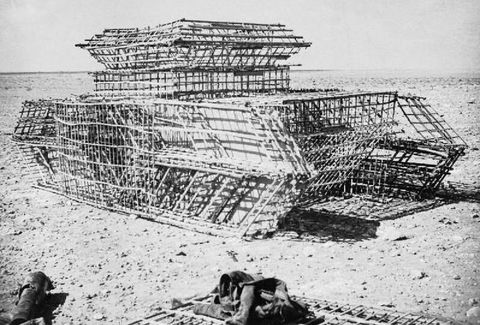

Whereas Operation Bertram was going to be Barkas’s present, most of the ways and classes that Penrose had outlined in his e book would come into play, from drawing enemy forces away from “important factors” to utilizing salvage supplies in creating dummy forces to protecting telltale army automobile tracks.

“I’m sure that Barkas learn [Penrose’s manual],” says Rick Stroud, the historian. Most of the parts outlined in Penrose’s handbook “would have been in Barkas’s thoughts,” he says. However Barkas was now charged with placing all of it into motion.

“He went out and flew out over the desert,” says Stroud, “and he started to work out that it’s not simply camouflage that’s wanted, however storytelling. It’s deception. And deception is the grown-up sister of camouflage.”

In simply six weeks, Barkas and his workforce created two dummy armored divisions— an outsized model of the “phantom platoon” Penrose had visualized in his handbook— in a south place within the desert, in hopes of luring German forces to assault them. Some 500 dummy tanks, 150 dummy weapons, and a pair of,000 dummy transport automobiles had been swiftly constructed.

Barkas’s workforce additionally went into overdrive to disguise the total power of the true British forces located to the north of the dummy drive. A whole bunch of tanks and big weapons had been camouflaged as vehicles. Though weapons, technique, and brute army drive would finally decide the course of the battle, equally essential parts included wire, nets, cloth, and miles of cotton string.

“It was the most important bodily camouflage operation of the battle,” says Stroud, “and just about all time.”

The big subterfuge labored. Uncertain of which military was actual, Rommel attacked each the true drive within the north and the dummy military within the south, dividing and depleting his personal forces. The victory at El Alamein was nonetheless painfully earned, regardless of this camouflage coup, but Montgomery’s forces prevailed, giving Britain a victory ultimately and a desperately wanted morale enhance. Churchill celebrated the position that deception had performed in serving to the Allies flip issues round, telling the Home of Commons shortly after the battle, “By a fabulous system of camouflage, full tactical shock was achieved within the desert.”

Barkas modestly said that though the battle had not been gained by “conjuring methods with stick, string and canvas,” he was glad that he and his workforce had helped “buy victory at a lower cost in blood.” Much less straight, El Alamein was additionally a victory for Penrose, Trevelyan, and the Surrealists world wide who had been selling, educating, and delighting in army camouflage for the reason that starting of the battle.

“They simply cherished loopy juxtapositions, cherished deception,” says Forbes. “They knew that they had been at battle, and that battle could be very critical enterprise, however additionally they one way or the other retained their inventive playfulness.”

The battle finally took an immense toll on the Surrealist group. After the liberation of Paris, most of the survivors, together with Miller and Penrose, reunited there. However “amid joyful reunions there have been ghosts,” says Antony Penrose. Miller had seen horrific sights in battle, hospitals, and focus camps and turned to alcohol to assist drown out painful recollections and experiences. Trevelyan suffered a nervous breakdown and was discharged from the army.

Mockingly, Surrealism itself—which had risen from the ashes of the First World Struggle and performed a small position in propelling the Allies to victory in the second—was additionally dealt a loss of life blow.

“Surrealism misplaced a lot of its impetus in the course of the battle,” mentioned Trevelyan. “It turned absurd to compose Surrealist confections when excessive explosives may do it so significantly better … Life had caught up with Surrealism or Surrealism with life, [and] we … lived the irrational motion to its loss of life.”

Antony Penrose says that Miller hardly ever spoke with him in regards to the battle: her trauma was too deep. But whereas Roland was additionally comparatively reluctant to reminisce about his wartime service, it was “evident that he did have a way of delight in what he had achieved,” says Antony. “He felt that it was a job effectively executed.”